Since it is no longer possible to separate urban politics and climate politics (if in fact it ever was), struggles for the right to the city are actually always struggles for a new socio-economic and ecological order to be built on the ruins of the previous mode of spatial production and capital accumulation. Both objects and terrains of eco-political struggle, cities are laboratories of planetary futures of human and other-than-human life, Florin Poenaru argues in his contribution to the “Kin City” series.

*

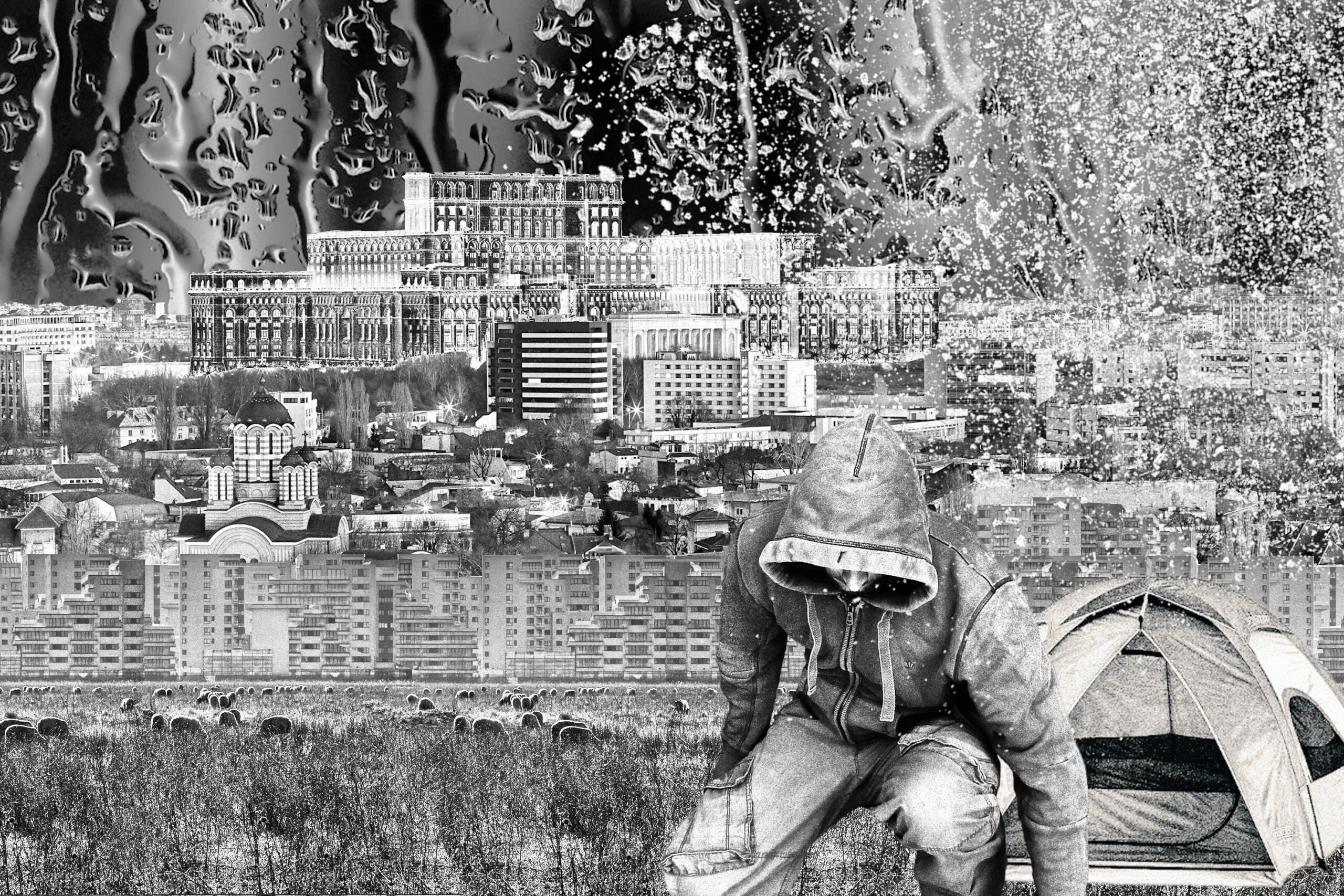

Cities, once celebrated as places of refuge from “barbaric wilderness,” are increasingly becoming inhospitable places for most of their inhabitants and, in the current situation of unbridled capitalist accumulation and ecological destruction, downright uninhabitable. This transformation towards general decay has a systemic cause: the prioritization of capital accumulation and speculation over the well-being of people and nature. Urban infrastructure has ceased to be a public, collective good (or at least an object of class struggle to maintain it as such) and has instead become the backdrop for capital investment under conditions of low profitability.

Life in general is negated as cities become closed centers of profit-making rather than places of human and other-than-human sociability. As a result, for example, more and more groups of people find themselves marginalized and ghettoized within a built environment over which they have no control and which is tailored to serve the interests of the capitalist class and its sycophants. This text highlights the relationship between urban transformation, capital, and human habitation in the context of global warming, while arguing for a reimagining of cities as places of refuge for all in the wake of collapse.

Explosion of urban logic on a global scale

In his 1970 book “The Urban Revolution,” Henri Lefebvre launched the hypothesis that society had become completely urbanized. At the time, it seemed far-fetched: only one-third of the world’s population lived in cities. What Lefebvre had in mind, however, was a new condition: the explosion of urban logic on a global scale; the affirmation of urban space as the main backdrop of capitalist accumulation. For him, this was a major break with the previous mode of capitalist production, namely industrialism embedded in nation-state economies.

Lefebvre used the concept of global cities as early as the late 1960s. This approach became standard in urban studies only in the late 1980s, when the emergence of global financial giants like New York, London, and Tokyo, due to the de-localization of industrial production following neoliberal economic restructuring, suggested the dawn of a new era in which global cities (not only in terms of size, but also in terms of economic and financial reach) would become dominant actors.

More than half a century after it was formulated, Lefebvre’s prediction no longer seems so fanciful: in 2024, nearly 60% of the world’s population will live in cities. The proportion of urban dwellers is expected to continue to rise. Planetary urbanization, as Neil Brenner calls this phenomenon with a nod to Lefebvre, continues in full force. But the process is uneven and heterogeneous. The Americas and Europe are highly urbanized (over 80%), as opposed to Africa (45%). Asia (53%) is highly unevenly urbanized, with Japan, South Korea and, of course, China leading the way. One result of planetary urbanization has been the unprecedented growth of megacities. Worldwide, there are 34 cities with more than 10 million inhabitants. Nearly 60% of the world’s urban population lives in one of these cities. In some cases, the rate of growth has been staggering. Beijing grew from 5 million people in 1980 to nearly 25 million today. Delhi jumped from 5 million to 30 million in a generation, while Mexico City more than doubled its population to 25 million in less than four decades. Dhaka, Sao Paolo, and Shanghai are projected to surpass 30 million by the end of this decade. It is important to note that planetary urbanization is a highly uneven and unequal phenomenon, leading to urban concentration and polarization similar to the economic and social polarization generated by the accumulation of capital in the hands of a few. It also leads to the formation of huge urban polities that are increasingly difficult to govern, organize, and live in.

Most urban growth has taken place on the fringes of the world’s major cities. This process, too, has been uneven and heterogeneous. Cities have exploded and urban fragments have flown like shrapnel, fundamentally transforming the space around them in diverse and contrasting ways: functionally integrated suburbs for the affluent; peri-urban developments that incorporate residential, industrial, and logistical functions; agglomerations of squats and favelas leading to what Mike Davis has called “the planet of slums”; “ghost towns” created by intense financial speculation; and various forms of dubaification, a process by which cities grow through megalomaniac projects in which land appropriation is key. Sometimes a city can concentrate more than one of these developments on its outskirts.

Take the case of Bucharest, the city in which I am writing this text and doing research. In the north of the city, there are suburban housing developments for the affluent middle and upper classes, combined with office space for the corporate sector. To the east and west of the city, there are increasingly large peri-urban areas that combine residential and service functions for the lower middle classes that cannot afford to live in the city core. The south is the most economically depressed area, combining “pockets of poverty” with logistics infrastructure.

The logic of urban capital

The intense concentration of population in and around certain hubs has led to the depopulation of others and the emergence of “shrinking cities.” The result is a hierarchically structured global geography of cityscapes in which inequality is rampant and growing. Big cities tend to get even bigger, while smaller cities continue to shrink. Skopje, Lisbon, Tokyo, Athens, Monrovia, and Dubai are home to about 30% of the population of their respective countries. About 35% of the population of Argentina lives in Buenos Aires, and the same percentage of the population of Lebanon lives in Beirut. Nearly half the population of Congo lives in Brazzaville, half the population of Israel lives in Tel Aviv, and half the population of Paraguay lives in Asuncion.

Although urban in nature, this growth generally lacks distinctive urban characteristics. One of the driving forces of urban expansion is the rent differential between urban and rural land. When land is transformed into urban land, it yields more capital to its owner. But this makes urban land more expensive and scarcer. Following this logic, there is little space left for public spaces and other collective amenities that characterize urban life: sidewalks, squares, hospitals, schools, and the like. Very high density is another key feature of the sprawl, leading to congestion, longer commutes, and pollution. This is why urban sprawl always seems to be an unfinished, transitory space.

But in the process of planetary urbanization, the cities themselves are changing radically. Lefebvre was well aware of this transformation. He wrote about the process of “embourgeoisement” of city centers, a process better known since the 1980s as gentrification. Neil Smith developed the notion of the “revanchist city,” the type of city that emerges from the process by which highly mobile global capital descends on cities and radically transforms them along the lines of profitability. Landlords, finance capitalists, landlords, real estate developers and retail conglomerates merge their interests and share the profits from the increasing privatization and ghettoization of urban space. The state, still relatively active in those urban centers that used to have a strong socialist and social democratic tradition, generally functions as an enabler of the radical transformation of cities along neoliberal lines.

One cause of the decline of the state’s ability to regulate and plan cities is that they are increasingly detached from their national economies and become sui generis global actors. The city-states of the Gulf region are only the extreme versions, with a very specific historical trajectory, of a global process of the rise of cities that become state-like. The constant urban development and redevelopment that characterizes all global cities is itself becoming an important economic activity: in other words, cities can generate their own (productive) economies by virtue of their own dynamics. It is precisely the most service-oriented global cities, disconnected as they are from any industrial activity, that have the capacity to grow their economies exponentially through land speculation and redevelopment.

No place for the poor

This transformation of the urban core has enormous consequences for its inhabitants. At the wrong end of the gentrification process, many are forced to leave cities altogether, swelling the ranks of the urban sprawl. Others, even less fortunate, join the growing ranks of the homeless. In 2021, the World Economic Forum estimates that approximately 150 million people worldwide will be homeless, while 1.6 billion will lack adequate housing. According to OECD reports, homelessness rates have increased in Denmark, England, France, Ireland, Italy, the Netherlands and New Zealand in recent years. In short: As cities grow, so does homelessness.

The downside of planetary globalization is restricted access to housing. This also violates the “right to the city” – another term coined by Lefebvre. Access to housing and the infrastructure of urban life in general is increasingly determined by the interests of capital: a large part of this infrastructure is in private hands, has been turned into the plaything of the markets, and is becoming more and more expensive. Consequently, most cities around the world tend to be structured along very clear lines: work and leisure infrastructure for the affluent classes within the city, on the one hand, and a large population of service workers employed to serve the former, who do not earn enough to live in the city and are thus forced to commute long hours each day, on the other. Unlike medieval towns or early capitalist cities, today’s cities have no place for the poor.

Moreover, precisely as a result of this constant pressure for “urban renewal” as the main means of capital accumulation, cities themselves begin to import features from the periphery, leading to a process of de-cityfication, a term I coined with my colleague Norbert Petrovici. By this we mean the loss of the characteristics of a city in the process of its restructuring by global capital and its associated interests: privatization of public spaces and their constant reduction (such as parks, gardens, sidewalks, etc.), increased densification, poorer public transport and greater reliance on private means of transport (not only cars, but also bicycles and scooters), lack of planning and regulation, and no development of social housing. This, combined with the increased cost of living in the city (which has reached unbearable levels, especially during the recent energy crisis), tends to turn cities into large, relatively uniform ghettos. The rise of digital platforms for a variety of urban services further usurps the functions and rhythms of the city, reinforcing the insularization and privatization of urban life. The generic coffee shop that looks the same from Tokyo to Berlin to Johannesburg, the urban “non-space” par excellence, to use Marc Augé’s phrase, is the insignia of late capitalist urbanization, in which the city itself is bound to disappear in the context of urban expansion.

As capitalist urbanization reaches planetary proportions and (global) cities become increasingly uninhabitable and inhospitable for the majority of their populations, romantic visions of urban escape and rural idyll once again dominate the public imagination. These romantic visions are juxtaposed with images of urban decay and ruin – a dialectic that has haunted the collective imagination of urban life since its inception. Closer to our predicament, Jane Jacobs lamented the death of American cities in the early 1960s. By today’s standards, they were the pinnacle of urban life. A number of reports document the descent of American urban life into chaos. Rebecca Solnit’s portrayal of San Francisco as the playground of Silicon Valley’s tech bros is particularly chilling.

But cities everywhere are experiencing a series of intractable problems in the current paradigm that make urban life a threat and a struggle, especially since capitalist-induced processes of urban decay are part of a vicious circle, as Magdalena Taube and Krystian Woznicki argue: “Ravaged and consequently revolting, ecosystems play back the stress to which they have been subjected; exposed to the feedback of the stress they generate [e.g. in the form of pollution or global warming], cities, as infrastructures of capital and life, are increasingly breaking down.”

Climate collapse as urban collapse

The ongoing climate collapse is likely to render a number of densely populated cities uninhabitable within a generation. Rising sea levels caused by global warming, for example, are a major concern. Jakarta, population 11 million, is sinking. So is Miami. The increasing number of extreme weather events (storms, heat waves, etc.) is also having a devastating impact on cities. For example, in 2023, storm Daniel caused a dam to burst, wiping out the Libyan city of Derna and killing tens of thousands. In recent years, several cities around the world, from China to India, Turkey, Iran, and the Arabian Peninsula, have recorded temperatures in the high 50s Fahrenheit. Barcelona introduced water rationing in the middle of the winter of 2023/2024 amid severe draughts. Other such cases abound around the world. Planetary urbanization on a warming planet poses unbearable dangers. And these disproportionately affect the vulnerablized, expropritated, and racialized, including the homeless.

This is the conjunction in which we find ourselves today: urban explosion (also reinforced by economic and climatic migration) accompanied by de-cityfication, declining city life and climate catastrophe. In short, planetary urbanization and disaster capitalism. “Who will build the ark?” Mike Davis once asked. Today, Darwinian ark and lifeboat fantasies are propagated by the right as it intends to exploit the apocalyptic condition. But there are alternative histories that can be traced back, for example, to the slave ship and its revolting masses of expropriated laborers, which, as Malcom Ferdinand suggests in his seminal book “Decolonial Ecology” (2022), can be harnessed to imagine and build a world-ship that enables emancipatory world-making.

Thus the question is: Can we activate this arsenal of alternative histories of colonial-capitalist modernity and redesign the urban form to function as a world-ship for all – a place of refuge, sociality, and solidarity? Lefebvre rightly noted that historically, cities have had a heterotopic foundation: caravanserais, throughfares, and marketplaces (in the broader sense, including carnivals and public theaters). Before the rise of the bourgeoisie as a dominant class, cities were places to escape the harshness and dullness of village life. Cities were islands of refuge for outcasts, adventurers, and lovers of freedom. Is it possible to rediscover this foundation of cities today?

Towards a new socio-economic and ecological order

The increasing unlivability of cities takes a toll on the physical, mental, and emotional well-being of their inhabitants. Crowded and polluted environments contribute to a wide range of health problems, including respiratory diseases and mental disorders. In addition, inadequate access to basic services such as health care and education perpetuates cycles of poverty and marginalization, trapping individuals in a state of perpetual precarity. As the infrastructure of capital continues to prioritize profit over people, the quality of life in urban centers deteriorates, leading to social exclusion.

Addressing the problematic relationship between the infrastructure of capital and life requires a fundamental rethinking of cities as inclusive and equitable spaces for all. This means prioritizing the needs of human and other-than-human life over the imperatives of capital accumulation, and investing in infrastructure that promotes social equity, environmental sustainability, and community well-being. Initiatives such as affordable housing programs, accessible public transportation, and green spaces can help mitigate the negative effects of capital-driven urbanization and foster a sense of belonging and agency among residents. Since it is no longer possible to separate urban life and climate consciousness (if it ever was), struggles for the right to the city are actually struggles to redefine a new socio-economic and ecological order on the ruins of the previous mode of spatial production and capital accumulation. Both objects and terrains of eco-political struggle, contemporary cities are laboratories of the collective future: either metropolitan eco-socialism or urban disaster capitalism.

Editor’s note: The article is a contribution to the Berliner Gazette’s “Kin City” series. More information: https://berlinergazette.de/kin-city-urban-ecologies-and-internationalism-call-for-papers/