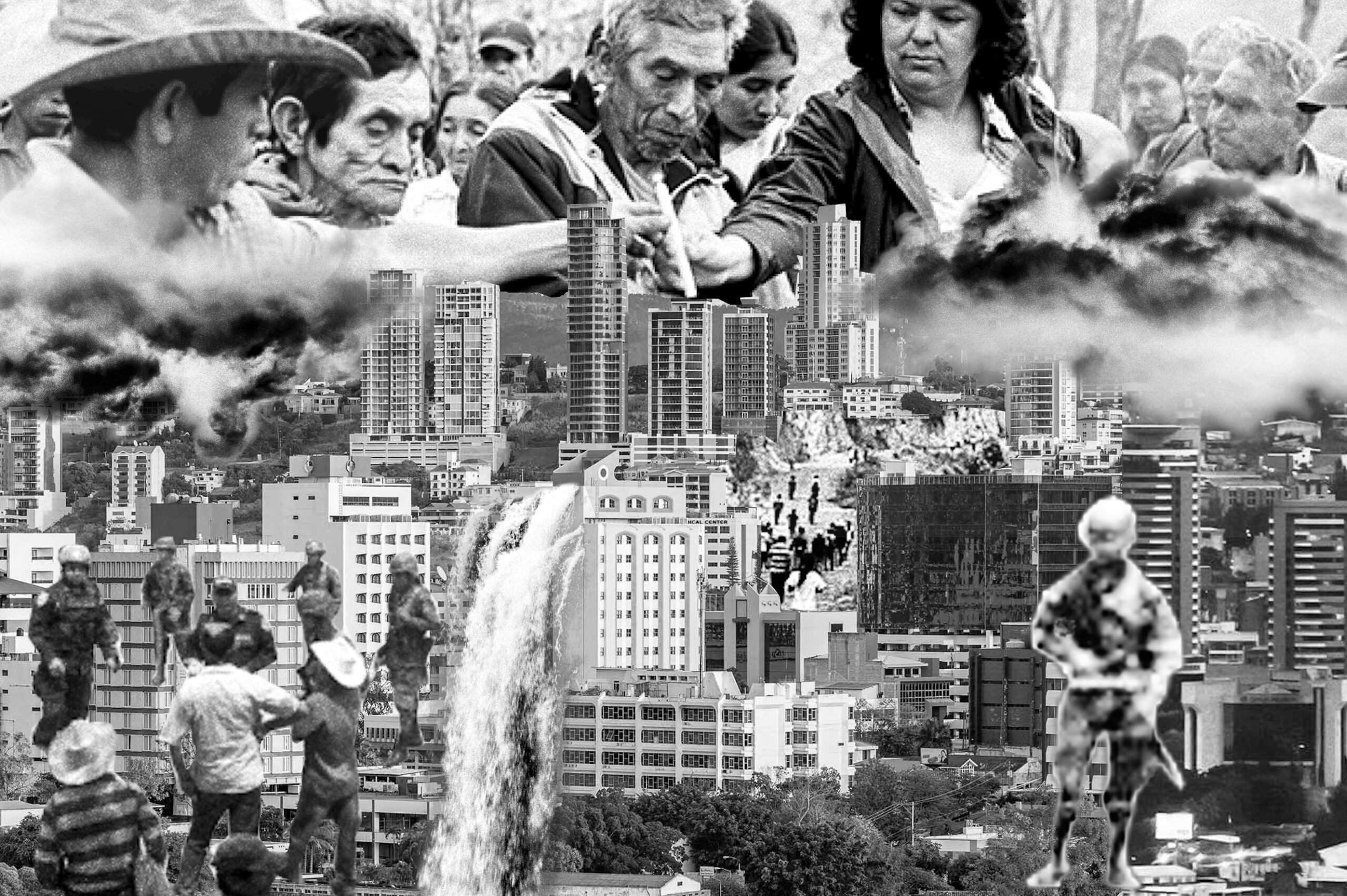

Since colonial times, Latin America has been central to the world’s supply of natural resources, and this remains true during the transition to “green energy.” Here, struggles against the predatory use of land and nature are always urban struggles: Social and political movements converge and reach a critical mass in metropolitan areas, as scholar-activist Simone da Silva Ribeiro Gomes argues in her contribution to the “Kin City” text series.

*

On June 5, 2022, the bodies of a Brazilian uncontacted tribes expert and an English journalist, Bruno Pereira and Dom Phillips, were found in the Brazilian Amazon. By then, after days of no communication between them and their families, a video had gone viral. In it, a relaxed Bruno sings a song with his Indigenous colleagues at his side in the Vale do Javaí. Bruno Pereira was a civil servant at the Fundação Nacional do Índio (National Indigenous Foundation). Dom Phillips was a freelance journalist doing research in the area. They were brutally murdered a few weeks earlier. Pereira and Phillips are among the 1349 Latin American social and environmental activists killed by state and paramilitary actors since 2012. Most of them were Indigenous men, significantly poor and acting with limited resources.

While deeply embedded in the forest, Pereira and Phillips’ interests and activism extend to other places and intertwine with activism in urban environments. This essay explores ideals and practices of resistance in the face of violent urban contexts in Latin America and how environmental struggles are situated within this scenario. After a quarter of a century, it is no longer a novelty that urban struggles are essential battlegrounds in Latin America, from the cosmopolitan urban feminist movement in Argentina, which has gained ground in the last decade with its Marea Verde (Green Tide), to the landless peasant movement in Brazil, led by the Movimento dos Sem Terra (Landless Workers Movement). The struggle for land is also urban, we have learned. These Indigenous, environmental, and feminist groups are making demands that at first glance do not fit into the conventional political framework, such as calls for the transformation of the state. While the causes are different, they are interconnected and transformed into more prominent struggles. This is the case with many of the activisms that have joined environmental concerns in the last decade to fight for climate justice.

Beyond challenging hierarchies of land ownership and ultimately being labeled as forms of resistance, one thing is certain: they take place or are connected to urban sites. Cities – where more than half of the world’s population lives – are not a minor matter here. In Brazil, the largest country in Latin America, about 87% of the population lives in urban areas. Argentina, Colombia, Peru, Uruguay and others follow.

Environmental struggles in Latin American cities

Environmental activism in the Global South has its peculiarities. Activists in Latin America are marked by their struggle to survive life-threatening situations, constant harassment, and assassination attempts by the state, landowners, and paramilitaries. No wonder that they formulate their (life) activism differently from the movements of the Global North. The defense of forests and the struggle for land are always linked to a broader discourse on justice over natural resources. As in many other contexts in the Global South, Latin American activists formulate their work in a more reactive way. Defending their rural or semi-rural territories is one way of acting. Other reactive ways include fighting for their lives in marches, occupations, public campaigns, and participating in the institutional politics that take place in the cities.

For example, at the time of her assassination in March 2016, Berta Cáceres, an Indigenous, feminist, and environmental activist, was leading the Consejo Cívico de Organizaciones Populares e Indígenas de Honduras (Civic Council of Popular and Indigenous Organizations of Honduras), abbreviated as COPINH, in the fight for the Gualcarque River. Like other Lenca Indigenous peoples, the existence of the sacred river they sought to protect was threatened by the construction of the DESA-backed Agua Zarca hydroelectric dam, which would prevent local access to the river. Berta was a fixture in Tegucigalpa, Honduras’ capital, marching against the 2009 coup that ousted Manuel Zelaya. Like Berta, four other COPINH activists have been killed since 2015.

In addition to the defensive stance often forced upon Latin American activists fighting for their feminist, Indigenous, labor, urban, and always, in some way or another, environmental causes, they also have one element in common: they act in cities devastated by neoliberal governance. The uprisings in Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Ecuador, Peru and Venezuela, to name a few, originated in rural areas in the 1990s. In these uprisings, the social structure that allowed movements to emerge had not yet been dismantled. The situation is beginning to change, and more recent urban uprisings indicate that opposition is emerging from sectors that are more heterogeneous than before.

The Global South is called to resist

In 1985, James Scott’s fieldwork with peasants in Malaysia gave a new meaning to the term resistance in the social sciences when he proposed the idea of everyday forms of resistance. His book “Weapons of the Weak: Everyday Forms of Peasant Resistance” described forms that included a hidden transcript. The covert resistance that elites could not see and could not easily capture, included subtle forms: boycotts, foot-dragging, theft and sabotage. These practices, used by peasants to navigate and undermine elite power, are almost invisible. The challenges included spaces beyond the control of the powerful, where neither surveillance nor repression could reach. This is partly why there is an indispensable rural component to the urban struggles in Latin America.

After nearly 40 years in the social sciences, the term has become hackneyed. “Resistance” is virtually everywhere, and its narratives are often used to analyze the activities of movements and activists when their task is difficult. To resist is what is asked of social movements and activists who face life-threatening situations and perform very difficult tasks. Sometimes it is too much to ask of people, as we Latin Americans know. But to engage in activities that are so internally diverse, as in social movements, taking into account one’s social class, race, gender, sexuality and nationality, is also to discuss what it is that we call activism.

Is the activism in the Global South different from that in wealthier countries?

Activism in social movement theory is a broad category. It includes social movements and people who are engaged in collective struggle for a period of time – or throughout their lives. However, people within collectives have different points of view, asymmetrical visibilities, and commitments to a cause. Because activism is also a generous category, it includes many people, whether they are teenagers in urban centers who are introduced to feminism through social networks, or peasants in land struggles on the Pacific coast of Central America. There is no entrance test to define oneself as an activist.

In urban contexts, formal aspects such as forms of organization, cycles of mobilization, and identity serve as a typology of social movements. Who is fighting for what and with what resources? While the urban poor may not formulate explicit demands with strategies and tactics, they are much more likely to be shaped by histories of violence and to wage their struggles on that basis.

Violence defines most of the activities in the Global South, because it also turns ordinary people with no previous experience in social movements into activists. The Mexican poet Javier Sicilia was living in Temixco when his son was kidnapped and killed by organized crime. Shortly thereafter, he founded the Movimiento por La Paz con Justicia y Dignidad (Movement for Peace with Justice and Dignity), which has achieved important legal victories since its inception. Peace movements in the Global North do not typically address drug-related violence, but in Latin America this is literally unavoidable, as the loss of a loved one is a common experience for those engaged in everyday struggles. In Argentina, Brazil, Guatemala, and Mexico, for example, mothers join collectives to search for the remains of their relatives who have disappeared and/or been killed by drug traffickers. Being an activist in this context is relentless work.

In such contexts, urbanization is disconnected from economic development, while the ongoing mode of accumulation displaces people from the countryside. The increased militarization of the urban periphery is partly responsible for the increased violence faced by activists – in the interconnected rural and urban contexts.

And how do these struggles differ from those in the Global North? The environmental justice movement in wealthier countries revolves around decarbonization, implementing zero waste initiatives, fossil fuel reduction, and degrowth. While all of these city-based environmental struggles are essential, there is a problem with their neocolonial energy basis. While activists agree that climate change is the existential threat of our time, the pressure to extract natural wealth and rely on cheap labor from the periphery continues. The Clean Energy North paradigm includes cobalt, lithium, land for large solar arrays, and infrastructure for hydrogen megaprojects. This is a new phase in the environmental plundering of the Global South.

Sensitivity to the hurdles that increasingly green activists in the Global South face, and the support they may need, means listening to issues of violence. The displacement of people due to dam construction, the implementation of green energy infrastructure such as solar and wind farms, security concerns, and reduced fish populations for fishermen are some immediate problems. Far-right governments are another.

North-South alliances?

All is not lost on the subcontinent. Violent struggles tend to generate civic engagement in ways that did not exist before. The global component of the climate justice movement is the lost connection of synchronous struggles taking place on an increasingly urban planet. The single struggle paradigm of feminist, pacifist, urban, land reform, and anti-racist struggles has given rise to ecofeminism, popular union feminism, Afrolatins, and North-South alliances. The cities will be the main stage – but the connection to the countryside will not go unnoticed in the activism of the Global South. This is the only way we will all be able to resist.

Editor’s note: The article is a contribution to the Berliner Gazette’s “Kin City” series. More information: https://berlinergazette.de/kin-city-urban-ecologies-and-internationalism-call-for-papers/