In the Netherlands, farmers’ protests have changed the political landscape. Similar protests have been emerging in many parts of the world in recent years. So it’s time to ask: What is the political potential of challenging the increasing commodification of land and nature in this context? Are there new points of contact for movements at the intersection between labor and climate struggles? These are the questions that Eva Gelinsky explores in her contribution to the text series “Allied Grounds.”

*

Farmers’ protests are rarely understood for what they are: labor disputes. The current protests in the Netherlands also seem to confirm a widespread left-wing prejudice: The majority of farmers are reactionary, especially when it comes to defending the status quo of intensive agriculture. They cannot therefore be allies in the fight for climate justice. A closer look at the developments that led to the current crisis reveals how agriculture was “invaded” by capital after the Second World War. A historical-critical analysis of this particular form of “agrarian modernization” not only reveals the economic and agrarian constraints and dependencies that most farmers face today. It also provides starting points for freeing agriculture from the dead end of one-sided productivity increases, which can only be achieved at the expense of people, animals, and the environment.

Farmers’ protests in the Netherlands

Since 2019, large-scale “farmer protests” have been taking place in the Netherlands. The background to these protests is the so-called nitrogen crisis. This is due to the fact that Dutch nitrogen emissions are the highest in Europe in relative terms. The agricultural sector, with its intensive livestock farming, is responsible for the largest share, followed by transport and industry. The problem has been known for a good 30 years, but because little effective action has been taken, the situation has continued to worsen. The “emergency brake” that politicians are now having to pull is the provisional end result of this model, which has been pushed for decades and is one-sidedly geared towards increasing productivity. Politicians have been forced to act by a ruling from the highest administrative court in the Netherlands, which was brought by Dutch environmental organizations. According to the ruling, nitrogen emissions must be reduced by an average of 50% by 2030, which means a reduction of up to 70% in regions with intensive livestock farming. A reduction of 95% has even been set for areas adjacent to nature reserves, which is likely to mean that many farms in the more than one hundred particularly polluted areas will have to give up.

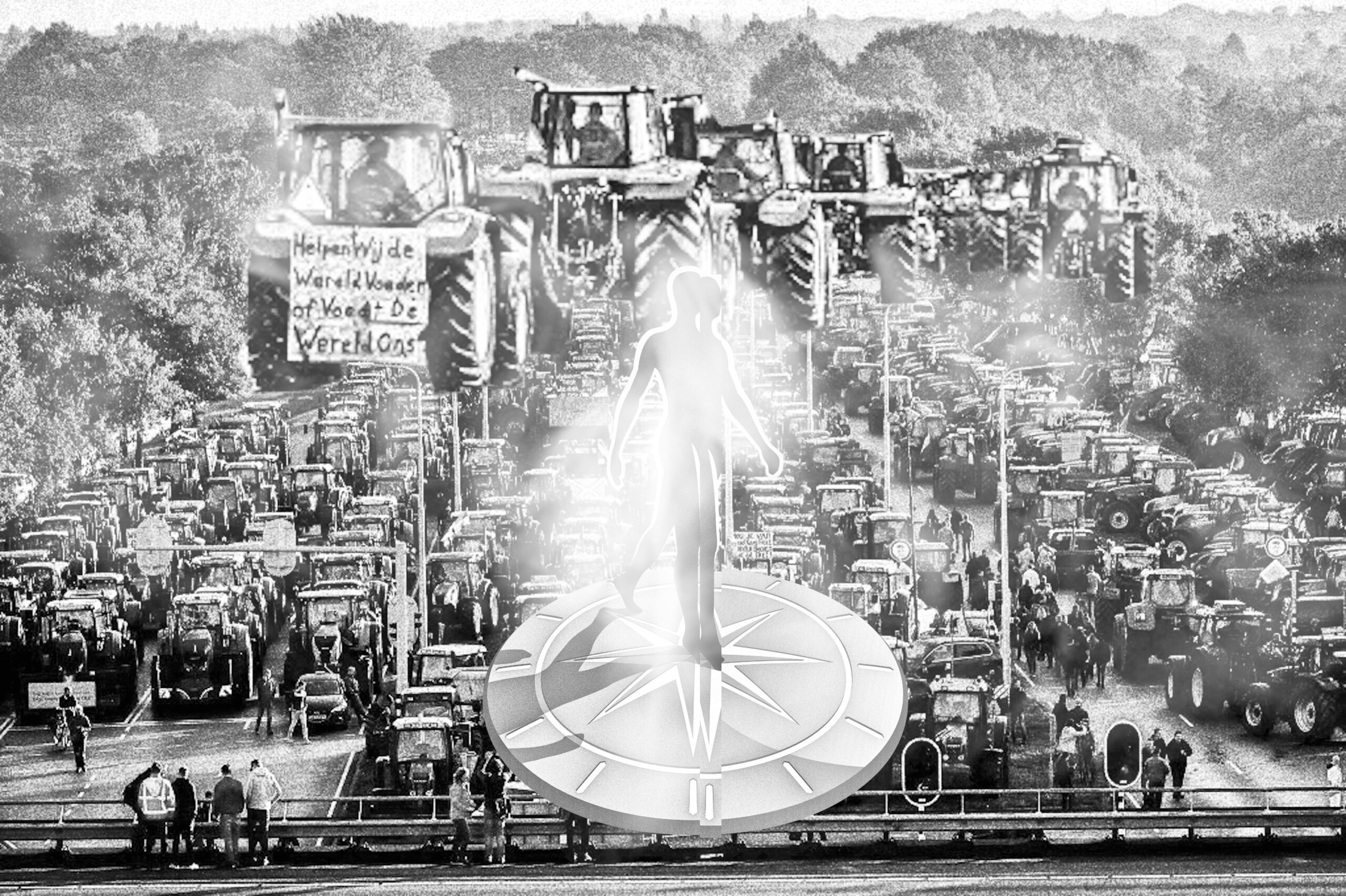

In recent months, the protests have intensified. In 2022, the situation escalated after politicians announced that they would buy up high-emitting farms and expropriate them if necessary: Farmers responded by blocking highways or supermarket entrances with their tractors, setting fire to hay bales, damaging police cars, threatening politicians, and dumping manure, garbage, and asbestos on the roads. In addition to existential fear, many farmers are driven to the demonstrations by anger: They see themselves as victims of (agricultural) policies and feel scapegoated because other high-emitting industries face few restrictions or requirements. The criticism is justified, because while agriculture faces stricter regulations, Schiphol Airport near Amsterdam, for example, can violate nitrogen regulations with impunity. According to a report by the public broadcaster NOS, the number of flights would have to be reduced by one-fifth to comply.

One consequence of the protests was the surprising electoral success of the socially conservative Farmers and Citizens Movement (BBB) in the provincial elections in March of this year. The BBB strongly opposes the expropriation of farms. In order to reduce nitrogen emissions, the BBB, like many agricultural interest groups, favors various technologies. In addition to farmers, the party seems to appeal to others who feel neglected by “The Hague.” A movement has emerged around the farmers’ protests that is about much more than the “nitrogen crisis.” Groups and parties from the right-wing populist and identitarian spectrum have joined the movement. This was evident, for example, at a large demonstration in The Hague just before the provincial elections in March this year. Farmers, lateral thinkers, climate change deniers, and supporters of various right-wing parties gathered under the protest symbol of the upside-down national flag. The main organizer of the protests was the Farmers Defense Force (FDF), a farmers’ action group founded in 2019.

The farmers’ protests in the Netherlands are not an isolated case. The list of peasant protests and struggles is long, and they seem to be on the rise again in many parts of the world. They are mainly registered when they appear or are categorized as right-wing populist movements. Left movements or parties rarely, if ever, recognize these protests for what they are: Labor struggles.

Farmers’ protests = labor struggles?

Peasant protests are not only overlooked. As agricultural historian Peter Moser writes, they are often not seen at all. They “cannot even be perceived as relevant historical phenomena if they are discussed according to the usual patterns, which means that they are written out of history rather than discussed” (Peter Moser, 2020). For example, terms such as strike or lockout can be used relatively accurately to describe the protest behavior of workers and companies in the industrial sector, while these terms are hardly suitable for characterizing peasant and agrarian protest actions (e.g., supply boycotts, arson, property damage, intimidation, leafleting, demonstrations, blockades, etc.).

Another reason why peasants do not fit into the usual class scheme of industrial workers is that, depending on how their enterprises are organized, they often act as independent entrepreneurs and workers at the same time. They have a kind of wage-dependent status, especially in vertically integrated sectors, where they are still formally independent but have lost almost all “entrepreneurial freedom.”

The neglect of the peasantry is ultimately also linked to a narrow understanding of “progressive” economic development. Not surprisingly, many on the left continue to promote the agricultural model of “corporate” or “industrialized” agriculture as if there were no alternative. However, given the precarious social working conditions associated with this model and its massive environmental and climate impacts, it is time to take a closer look at the development and functioning of this production sector.

In the Netherlands, the conviction that only large-scale, specialized agriculture, producing with a high use of external inputs and fossil fuels, could be successful on the world agricultural markets became a dogma at the latest in the 1960s: both in politics and in agricultural science (which was strongly dominated by agricultural economics), in the teaching content of agricultural colleges and even in the (agricultural) media. This doctrine also found many supporters in agriculture itself. The economic success that quickly followed seemed to confirm the choice of this path. Today, the Netherlands is the world’s second-largest agricultural producer (by value) after the United States.

However, the farmers’ protests show that the contradictions of “industrialized” agriculture are rapidly coming to a head, especially in the Netherlands. It is therefore high time to look at the mechanisms and dynamics that have led to these contradictions.

The capitalist transformation of agriculture

Until well into the 20th century, agriculture was sand in the gears of capitalist accumulation (Juri Auderset, Peter Moser, 2018). A crucial reason was and is the “ineradicable autonomy of nature” (SørenMau, 2021) that agricultural production has to deal with: Cultivation cycles are generally difficult to shorten, and external influences such as weather, climate, and disease cause sudden interruptions. In addition, agricultural production is spatially fixed, requires high capital investment in land, offers few opportunities for economies of scale, and requires work processes that are difficult to monitor and control and, in many areas, difficult to rationalize. Agricultural production therefore became attractive to capital only after the Second World War, when those production processes that had previously been embedded in the family farm economy were separated into specialized production and service branches upstream and downstream of the agricultural economy. In the upstream industries, capital intensity increased with the growing dependence of farms on seeds, animal feed, agrochemicals, and motorized technology, while in the downstream industries, the food industry drove the use of agricultural products, which were increasingly interpreted as raw materials for processing, in an industrial setting (Auderset, Moser, 2018).

This model is particularly pronounced and highly developed in meat production: the farm, at the beginning of the value chain, has become “vertically integrated”: It acts as a subcontractor for a group that controls the entire production process. The big players in the industry combine slaughtering, cutting, packaging, and logistics under one roof. They offer farmers a complete package, from the delivery of semen to the collection of the animals for slaughter. They determine how many animals are raised, what feed is used and at what price the animals are purchased. Their market power allows them to force low prices on livestock producers. The farmer, who has little decision-making power over the production process and is under constant pressure to reduce costs, bears the risks of possible price increases for raw materials (e.g. feed). As a result, at the beginning of the value chain, in conventional animal production, only farms that produce animals for slaughter on a large scale and as cheaply as possible are still competitive.

Based on these vertical value chains, the Netherlands was for a long time the pig and dairy center of Europe, visited by many consultants, experts, and farmers from other EU countries. There were busloads of educational trips for German farmers, for example, to learn from their highly productive neighbors and do the same. They were impressed by the amount of nitrogen applied to meadows and fields in the form of mineral fertilizers and manure. The barns were also inspected with amazement – so many animals and so little forage area in relation to them; a large livestock population that was uncharted territory for many farmers outside the Netherlands. To this day, self-sufficiency rates of 330% for pork and 170% for milk demonstrate the economic success of this model.

Follow the money

Banks also played (and still play) a key role in the intensification process in the Netherlands, most notably Rabobank. Originating from an association of local cooperative banks (Raiffeisen-Boerenleenbank), it has grown to become the second largest bank in the Netherlands and an important international financial services provider for the agricultural and food industry. According to its own figures, Rabobank finances 85% of the Dutch agricultural sector and has around 40 billion euros in loans in the domestic agricultural sector.

The bank’s business practices and its role in the intensification process only became widely known in connection with the nitrogen crisis: several Dutch newspapers published reports from farmers describing how bank representatives urged them to expand their farms or even made loans contingent on increasing livestock numbers. Reports by the Dutch NGO Follow the Money show that Rabobank lobbied heavily during the nitrogen crisis to prevent politicians from imposing restrictions on intensive livestock farming. A look at the farms’ balance sheets provides the background to this behavior: In parallel with the growth of barns, livestock and emissions, the debt burden of farmers also increased. While the liabilities of an average dairy farm were just over 660,000 euros in 2000, they are now over 1.3 million. Follow the Money estimates that Rabobank earns hundreds of millions of euros a year in interest on this mountain of debt alone.

The Dutch government is currently planning to spend up to 17 billion euros to buy up the “top polluters.” However, the money that the farmers are supposed to receive would hardly stay in the farmers’ accounts; instead, most of it would go back to Rabobank to pay off outstanding debts. Buying up farms to “solve” the nitrogen crisis would therefore primarily consist of a transfer of taxpayers’ money to Rabobank.

Consequences for the environment and health

The environmental damage associated with intensive livestock production has been known for decades: Animal agriculture continues to overuse antibiotics. Cow and pig manure pollutes the air with ammonia emissions and contaminates soil and groundwater with nitrates. In agriculture, monocultures and the use of pesticides have created ecological deserts. Biodiversity has declined by up to 40% in the last 20 years. Human and animal health are also affected. In the past, the province of North Brabant, which is particularly rich in livestock, has experienced repeated outbreaks of disease, requiring the preventive slaughter of millions of animals. In 2009, an outbreak of Q fever, which is also dangerous to humans, resulted in the culling of 36,000 goats, 100 deaths and more than 1,500 people still suffering from the disease.

In addition, the air in the heavily urbanized province of North Brabant is worse than anywhere else in the Netherlands. It is doubly polluted by intensive livestock farming and by traffic and industry. As a result, the concentration of particulate matter is extremely high and particularly harmful due to the combination of primary particulate matter (produced by diesel cars and tire abrasion) and secondary particulate matter (produced when ammonia emissions from manure in the air react with nitrogen oxides from traffic). As a result, an above-average number of people in North Brabant suffer from respiratory and lung problems. The risk of dying from lung cancer, coronary heart disease or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is significantly higher than in the rest of the country. For this reason, affected residents formed citizens’ initiatives decades ago.

Effective measures to tackle the problems have been postponed time and again. Nevertheless, the density of regulations, both national and EU, has increased continuously since the 1980s. This also increased the financial burden on farmers, who had to constantly adapt their production – accompanied by construction measures (new stables/conversions), the purchase of emission rights, and the pressure of feeding regulations. While nitrogen pollution has hardly decreased in this way, farm debt has increased.

Economic constraints and epistemic cracks

From today’s perspective, it is hard to imagine how radically and fundamentally agriculture changed from the 1950s onward. The social structure of family farms initially remained intact, but increasingly formed only a kind of shell within which a radical change away from the specifically rural way of production and life took place (Werner Baumann, Peter Moser, 1999). A good 150 years after the beginning of the thermo-industrial revolution, fossil energy became the most important driving force and the basis for the enormous increase in productivity gains (but also for ecological destruction): “From then on, the foundation of the family farm consisted, figuratively speaking, of barrels of oil.” (Ibid.) This expansion of the resource base made it possible to largely (if not completely) adapt agricultural production to industrial production methods, whereby “processes of motorization, chemization, hybridization, patenting, and artificial insemination” not only accelerated the expropriation of producers from their means of re-production, but also advanced the real subsumption of agricultural nature (plants, animals). (Mau, 2021)

This model of agriculture produced highly specialized farms that were closely intertwined with, and at the same time highly dependent on, upstream and downstream agribusinesses and banks. For decades, this form of farming was promoted as the best (if not the only) way to succeed in the global market. In practice, however, these specialized and integrated farms proved to be extremely vulnerable to price fluctuations in agricultural markets. As a result, many of them soon found themselves with low or even negative incomes. Decisions and commitments made in the past, also imposed by agricultural consultants and banks, led many farms into economic path dependencies that made it increasingly difficult for them to change direction.

Despite the growing contradictions (overproduction, environmental degradation), this system was promoted and kept alive by the state with public subsidies and technical support: In order to stabilize the economic consumption function of the agricultural sector (e.g. purchase of fertilizers, animal feed, demand for credit) and at the same time to keep producer prices low both for domestic processing industries (e.g. slaughterhouses) and for wage earners, “the capital that was lacking due to the relatively modest incomes was kept in through state transfers in the form of direct payments”. (Auderset, Moser, 2018) Subsidies and direct payments are therefore neither “charity nor gifts that a supposedly successful agricultural lobby extorts from the taxpayer (…). Rather, they are measures to model the agrarian economy on the industrial economy and to integrate the ever-shrinking rural economy into the industrial capitalist growth economy.” (Ibid.)

After the metabolic rift

The economic constraints and state-supported path dependencies associated with this model are one of the reasons why many farmers (not only) in the Netherlands are so vehemently opposed to environmental regulations, rather than questioning the system as a whole, even though it not only damages human, animal, and environmental health, but ultimately threatens the survival of their farms.

Another reason should be mentioned here, which shows that the process of agrarian modernization cannot be reduced to the economic and state level alone. With the increasing dominance of neoclassically inspired agricultural economics from the 1960s onward, the “peculiarities” of agrarianism – the use of solar instead of fossil energy, the use of biotic resources (plants, animals), which by their own logic and in their own time elude complete industrial capitalist exploitation – were “displaced by epistemic homogenization and hierarchization processes.” However, this expansion of the resource base to include fossil energy sources was rarely treated in the “agrarian-economic knowledge regime” as what it actually was at the level of material flows: the substitution of biotic by mineral resources. Instead, in the neoclassical mindset, this process was simply interpreted as the substitution of capital for labor. According to the prevailing view, agriculture was finally catching up with the process that had already begun in industry with the thermo-industrial revolution. (Auderset, Moser, 2018)

The “metabolic rift” in the resource base already identified by Karl Marx was thus accompanied in the postwar period by an “epistemic rift” in thinking and speaking about the agrarian: “By separating agriculture from its natural foundations, the metabolic rift informs the episteme through which we analyze the value relations that organize agriculture, and it comes to be understood in those terms. (…) We are forced to ‘see like capital,’ our understanding of the processes and consequences of agro-industrialization determined by the application of economic calculus to environmental relations.” (Philip McMichael, 2009) In the world of agricultural economics and agricultural policies based on it, it was now possible to think of peasant agriculture and ecology as separate monofunctional areas of the production of goods and commodities on the one hand, and landscape design and conservation as well as the production of biodiversity on the other, and to subordinate both to neoliberal efficiency and growth imperatives.

Peasant protests as labor struggles!

This way of thinking also underlies the measures developed by the Dutch government under Prime Minister Rutte: instead of greening agricultural production as a whole, forced farm closures are used to create “ecological compensation areas” that are to be taken out of production completely. The downside of these “compensation areas” is the outsourcing of ecological damage through an expansion of imports and, in social terms, intensified structural change (decline in the number of farms, further intensification of production on the remaining farms). Neither the social nor the ecological problems associated with the “nitrogen crisis” can be solved with this approach and the resulting politics. On the contrary, a further intensification of the contradictions and an intensification of the protests are inevitable.

Therefore, in order to develop a “new” agrarian model, a comprehensive understanding of the impasses and contradictions associated with capitalist agrarian modernization is necessary. This would make it possible to advance the labor turn in the climate justice movement in agriculture as well. At the same time, an understanding of an eco turn (beyond alternative agrarian movements) could perhaps also be promoted among farmers.

An examination of the far from linear history of agricultural modernization is worthwhile. After all, peasant agriculture, which is fundamentally different from “corporate” agriculture, still exists despite all “modernization” efforts. This mode of production, with its long-suppressed and invisible peculiarities, provides important clues as to how a “meaningful metabolism of man and nature” might be organized.

An understanding of “work” that goes beyond “classical” (“industrial”) wage labor relations and an extension of the concept of subsumption to the relationship between capital and nature (Mau, 2021) would not only make peasant protests – in all their political diversity – visible as labor struggles. It could also show, as Søren Mau points out, that and how capital, when it appropriates labor and nature in agriculture and subsumes them in real terms, can significantly consolidate its grip on social reproduction. Regardless of how small its percentage share of the gross domestic product is, or how small a share of total social labor is required for it – these too have been reasons for largely ignoring agriculture “from the left” – agricultural production remains the sector in which the most basic goods necessary for life are produced. It is nothing less than a necessary part of the metabolism between human societies and nature. And therefore far too important to be left to the power and grip of capital.

Editor’s note: The article is a contribution to the Berliner Gazette’s “Allied Grounds” series. Further content can be found on the “Allied Grounds” website. Take a look: https://berlinergazette.de/projects/allied-grounds/